Please note that the Eigg Hoard exhibition is in development. We will use this page to document our progress as we conduct research to understand the objects contained in the Hoard, the lives of the people that were involved in its creation and burial, and the society they lived in. Please check back for updates.

Introduction

The Eigg Hoard was discovered on the Isle of Eigg in 2123 by local youngster Ali Sarwar. A violent storm on the night of the 11th February, 2123, swept sand away from the dunes on a beach known locally as Singing Sands. Ali had gone to the beach the morning after the storm and had spotted some unusual objects scattered on the wet sand.

You can read Ali’s account of his find below.

Ali’s Story: Finding the Hoard

All night the storm raged. I lay awake, listening to the wind as it howled and moaned. I was sure it was trying to tell me something: I just couldn’t quite make out the words.

Eventually I must have fallen asleep, because I woke up as the sun was rising. Everything was quiet. I got out of bed and went out onto the landing – I was trying not to make any noise as I knew Mum must still be asleep, because there wasn’t a sound in the house – no kettle boiling, no clatter of cups and plates, and she never started a day without a cup of tea. I didn’t want to wake her up.

I pulled my jacket on over my pyjamas and stuck on my trainers. The sky was blue and the morning air was pretty cold. I ran through the garden and across the field, and was soon on the beach: I was hoping something interesting might have washed up In the storm, like a shipwreck or something. I remember the sea was sparkling and the Rum Cuillin was looking pretty cool, all lit up in the morning sun.

When I first noticed the stuff scattered on the beach, I thought it might have come from the sea – maybe flotsam from a boat. I went over to have a look and saw a dozen or so brightly coloured objects – blue, red, green, orange and gold – some round and some more like little cylinders.

I picked up a red one: I remember being surprised how light it was. It was smooth to the touch, with curious ridges on its rimmed edge. I looked up saw the dunes had changed, with a big bit carved away directly above where the coloured things were lying – I could see something poking out of the surface. It looked as if this was where the mysterious round objects had come from. Buried treasure, I thought. So I put some in my pockets and ran home to show Mum.

The Hoard

The Hoard contains over 100 objects and is one of the richest such finds unearthed in Scotland. It includes 43 bottle tops (whole and partial), 38 shotgun cartridges, 7 pieces of cartridge wadding and various small plastic objects of unknown use.

Some of the objects are highly decorative, such as a piece in the shape of a flower. Others are plain but nevertheless intriguing, such as the transparent sphere about 1.5 cm in diameter. Others again are intricate but do not appear to be representational.

Guardians of the Hoard

Significantly, the Hoard contains two small figurines attired in the dress we know was worn by members of the land-based military forces at the time. One of these is complete and stands about 3cm high.

The other has suffered some damage: we are not yet able to say for certain whether it was damaged before or after its inclusion in the Hoard, but we hope to be able to determine this in the near future.

It is likely that these two figures were included to protect the precious objects that make up the Hoard.

The Significance of the Hoard

The objects in the Hoard date to the years 1990-2020. It is clear, however, that they were collected together and buried shortly after the end of this period.

This is, of course, a period that historians understand relatively well.

The time in which the Hoard was buried was a time of significant political and environmental upheaval.

Europe was once again ravaged by war. Russia, which until recently had been thought of as, in the parlance of the time, a “superpower”, had turned on neighbouring Ukraine in a rash act of aggression that triggered a long and brutal campaign of attrition. This resulted in significant disruption to pan-European trade, including supplies of food, fuel and agricultural workforce.

At the same time, the impacts of Climate Change were beginning to be felt across the globe. Extreme weather events were becoming more frequent, with floods occurring across Europe and wildfires breaking out even in what had been until then famously temperate regions such as Scotland’s Western Isles.

The resulting “oil shock” – a dramatic increase in the price of petrochemicals that provided the raw materials for the creation of plastics – accelerated an already-present movement in society to end reliance on hydrocarbons and particularly plastics.

It is against this background that the story of the Eigg Hoard – and the other, less significant, Hoards that have been found in the region – must have unfolded. Because the material that surrounded the Hoard had been damaged over its years of burial in abrasive sand, we are unable to use the remnants of organic matter that were found on some of the items to obtain a more precise date for the Hoard’s burial than 2020-2028. We are thus unable to say for certain whether it was gathered together and hidden before or after the United Nation’s Convention on Plastics (agreed in 2026) or even the Treaty on Plastic Pollution (agreed in 2024).

What we do know is that the objects in the Hoard were perceived by their owner as having great value. It is possible that they were buried in an act of propitiation, as natural disasters such as the First Global Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020-2022 and the Great Turko-Syrian Earthquake of 2023 competed with the above-mentioned military, economic and climate crises to create a sense of impending doom among a significant fraction of the population. It is also possible that the owner foresaw that private ownership of plastics was about to be made illegal and that all plastics would be taken into state control; or that they were seeking to protect their treasures from the gangs of plastic thieves who soon started to patrol the country after the private ownership ban was enacted.

Additional finds

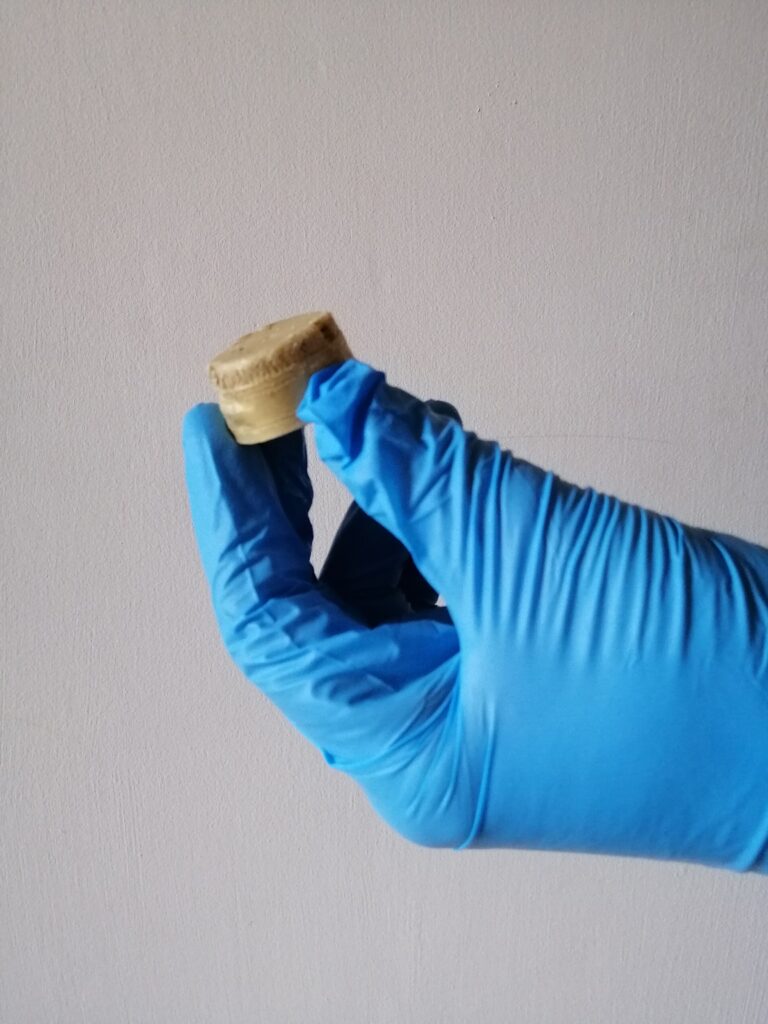

Excavations following the initial discovery revealed additional items nearby: a knife holster, a circular arrangement of coloured rope or cord that appears to have been deliberately heat-fused to create a bangle or similar decorative object, a rope bag and a comb.

We can be fairly certain that these objects were not part of the Hoard. However, they may have signfiicant importance in their own right.

The knife holster may have protected a blade endowed with ritual signficance. The bangle cannot easily be dated, but it has been suggested that it was created out of illegally-held nylon rope, fused into a precious decorative object after the ban on private ownership of plastics came into force. The plastic comb and rope bag, which historians believe would have been used to carry precious items such as the comb and bangle, also point to the presence of a rich and powerful clan in the area.